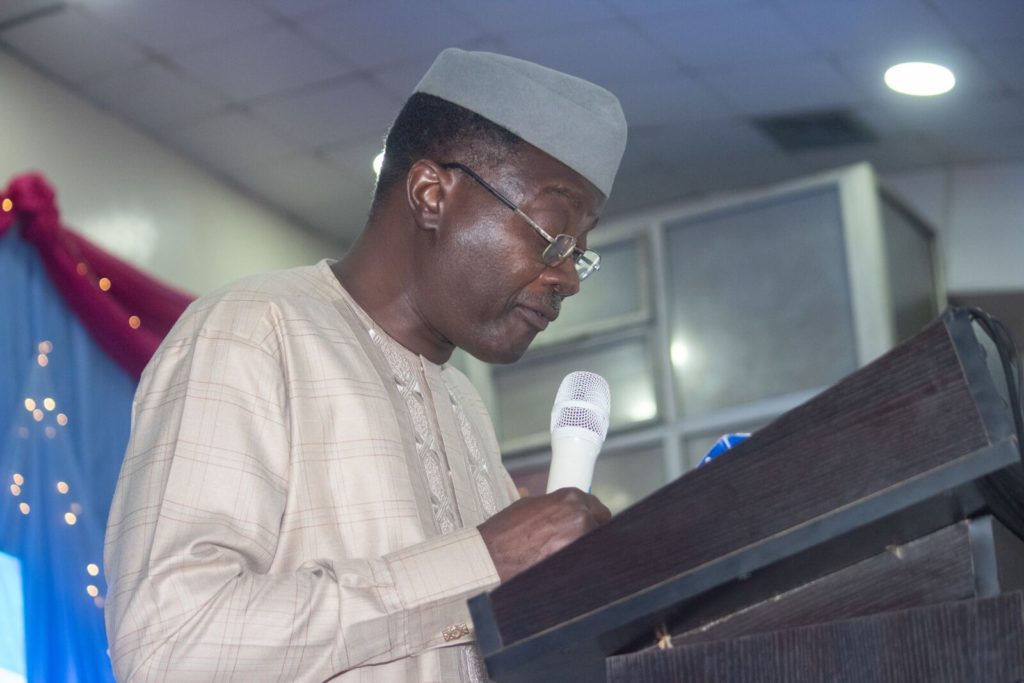

Mr Kunle Ajibade, Executive Director of TheNEWS/P.M.NEWS, read this review at the public presentation of Lanre Arogundade’s Media and Election: Professional Responsibilities of Journalists on 16 July 2019 in Lagos.

Exactly forty years ago last month, one of Nigeria’s best journalists and editors, the assassinated Editor-in-Chief of Newswatch, Dele Giwa, wrote a piece in his popular column in Sunday Concord when it was clear to him that reporters on the political beat in Nigeria were not reporting well. He argued that ‘‘in writing political analysis for the newspaper the reporter will not have the license to take sides with any of the contestants. He will be expected to be as impartial as humanly possible in analysing the political and campaign strategies of the candidates in a political race. In other words, a reporter covering a particular candidate should be able to give readers details of the candidate’s plans and method for winning the voters to his side.

He will write from his understanding of the candidate, having spent time following him on the hustings and having digested every one of his speeches and position papers of his party. The reporter will be expected to understand the candidate’s issues and see whether they are pertinent to the needs of the nation. And then, he must watch carefully how the candidate presents his issues to different segments of the electorate. Are the candidate’s promises outlandish? Will they help the nation? Does the country have the resources to fulfil the promises?

The reporter must ask these questions in his stories and find answers to them by talking to experts in the fields concerning each issue and promise and then probe the electorate’s reactions to them. Journalism has gone past the stage in which all a reporter does is to report what a man says. Yes, doing that is basic to his calling but he must then take what the candidates are saying to critical and objective analysis. It’s not too late to start talking about the drive behind the candidates, that they have not been debating issues and that they are talking over each other’s heads down to the electorate. Voters in this country would still like to know the weaknesses and strengths of the candidates, their resilience and temperament and the character of their advisers. We have heard all the promises but are the candidates disingenuous in making some of them? The political reports must tell us.’’

That was in June 1979 in the heat of the campaign leading to the short-lived Second Republic. That was long before the enactment of The Electoral Act 2010, The Nigerian Broadcasting Code, and The Nigerian Media Code of Election Coverage that has now spelt out in clear terms the responsibilities of a political reporter. The sloppy political reporting that Giwa complained about in 1979 is one of the major planks of Hillary Clinton’s very interesting memoir on the election that brought Donald Trump to power in the US. One page 223 of What Happened, the title of her sobering book, Hillary says, ‘‘The decline of serious reporting on the policy has been going on for a while, but it got much worse in 2016. In 2008, the major networks’ nightly newscasts spent a total of 220 minutes on policy.

In 2012, it was 114 minutes. In 2016, two weeks before the election, it was just 32 minutes. By contrast, 100 minutes were spent covering my emails. In other words, the political press was telling voters that my emails were three times more important than all the other issues combined.’’ In case you think like Donald Trump that Hillary the Democratic Party presidential candidate is saying this because she is a bad loser, credible studies from top universities in America have consistently shown that healthcare, taxes, trade, immigration, national security, education, infrastructure, agriculture, etc., etc., got only 10 per cent of the press coverage. None of Donald Trump’s scandals generated the kind of sustained, campaign-defining coverage that Hillary Clinton’s emails did. To a large extent, therefore, it was the irresponsibility of political reporting that paved the way for Donald Trump over a highly credentialed, highly experienced Hillary.

I’m prepared to argue this point with anyone who disagrees with me from now till tomorrow. Hillary only lost at the Electoral College with a small margin. Today, the whole world is suffering from the dire consequences of that irresponsible political reporting. Hillary, who tempers her rage with hope and optimism in her book, is no longer the casualty. Her loss, as painful as it is, will not reduce her enviable achievements; it will not diminish her significance. The casualty, in the main, is the future of our world in the hands of a rotten character, a shallow-minded narcissist, a racist, a serial liar, a shameless molester of women and an insufferable, irredeemable crook. The reason I’m referencing Giwa and Clinton should be pretty obvious to this gathering. Both of them, in the passages that I’ve just quoted, affirm the immense power of the media and suggest that the power should be wielded with an absolute sense of duty.

What Lanre Arogundade has done creditably in Media and Elections: Professional Responsibilities of Journalists is to show us how to wield the power gracefully, in a way that will make us fulfil the promise that our constitution imposes on the Fourth Estate of the Realm. If the book is comprehensive in its listing of dos and don’ts of election coverage, it is because Lanre has spent many years of his adult life fully engaged, fully involved, in politics as a student union activist, as a journalist, as senatorial candidate, as a media trainer, as an editorial writer, as an election observer, and as an author of several resource books on institutions that will strengthen democratic values in Nigeria. This book, then, is a product of intense practical experiences of an honest and patriotic witness. If Dele Giwa wrote in simple and truly enchanting prose in his piece that I have just cited, Lanre Arogundade sometimes writes in this book with the turgidity of a workshop expert who has come to town with a truckload of theories. Don’t get me wrong. He has not written as an expert with multiple jargons but as an expert who wants his message to be easily understood.

Without boring the reader, Arogundade takes us through the electoral history of Nigeria as a way of setting the tone of his important subject. If elective democracy was introduced in 1919 in Nigeria, he observes, it means that 2019 elections marked the centenary of elections in our country. From 1919 to 2019, Arogundade traces the trajectories of elections in Nigeria, signposting the ones under the colonial rule and the post-independence elections which ushered in both Parliamentary and Presidential systems of government. What interests him in narrating the history of elections in Nigeria is simply that all the way Nigerian journalists have always been there to report these elections since the first newspaper in Nigeria was founded on 3 December 1859. What the record shows is that as much as today’s political reporters share the patriotic zeal and will of their forerunners and pathfinders, they also share their professional misconduct for they all have contributed to the recurring cycles of electoral violence and stupidities in our country with their reports. Specifically, journalists escalated the post-election violence in Western Region in 1964; in the South West in 1979, 1983 and 19993; in Northern parts of Nigeria in 2007 and 2011; and in many parts of the country in 2015 and 2019. Why did it all happen? Arogundade says that the media which ought to be impartial umpires, that should serve as mediators in the electoral processes descended to the dirty arena of partisanship with their deliberate incitement of violence, lack of equitable coverage of parties and candidates, fake news, sensational headlines and hate advertorials.

All of these, of course, contradicted the broad tenets of The Nigerians Media Code of Election Coverage, the principles of The Electoral Act and the expectations of The Code of Ethics of Journalists in Nigeria. Lanre Arogundade believes that it is wrong to assume that political reporters who breach the code of conduct understand fully what the terms entail. To this extent, the author, with the dash and verve of an experienced capacity builder, guides us through what it takes to do responsible and excellent election reporting. With facts, figures, graphs, theories, anecdotes and explanatory statistics, he discusses illuminatingly balanced, inclusive-sensitive, issue-focused, electoral processes, post-elections accountability reporting and the necessity for factual accuracy in the reporting of elections. Relying heavily on The Nigerian Media Code of Election Coverage as his backrest, Arogundade tells us that for a journalist to report elections accurately, without bias, in a fair and balanced manner, he or she should gather the news from reliable multiple sources who are willing to provide factual evidence.

Another essential ingredient of balanced reporting, he posits, is that the journalist should eliminate biases from his reporting. “What is expected’’, Lanre Arogundade writes, ‘‘is that the good election reporter must understand his or her bias and refrain from allowing such to affect his or her news judgment, gathering and dissemination.’’ Equitable coverage of all political parties is yet another ingredient of balanced reporting. During elections, the tendency is to cover top-shots of major political parties, but Arogundade argues that this kind of election reporting is not complete without paying attention to the under-represented groups such as women, persons with disabilities and the large number of our people living in the rural areas. Allied to this is the need for the election reporter to be so informed that he knows what the issues are so that he can call attention to them and, if necessary, set agenda with his reports.

Arogundade gives many tips on conflict reporting during elections. According to him, since the election is a means through which people express diversities which are always conflicting in nature, it is critical that reporters covering election see themselves as agents of mediation, engagements and amicable interventions. There is a long list of what to do in this book to develop the antennae for careful reporting of conflicts during elections. When elections are over and governance starts in earnest, that’s the time to call those in the saddle to proper accounting. Which of the promises are fulfilled, and at what cost? Which of them are broken? To do this is to be a conscientious functional member of the Fourth Estate of the Realm. And as the political reporter does all of these, accuracy, imbued with fact-checking mechanism, should be the watch-word. Needless to say, all these rules apply to reporters who cover other beats as well.

Finally, let me end with Thomas Jefferson the third president of the United States of America, who is quoted by Lanre Arogundade approvingly, in this book. Jefferson, one of the Founding Fathers of the US said: ‘‘Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.’’ That, in a sense, captures the spirit of this book. And it is a spirit that celebrates the power of the media. Yet if you have enormous power and you don’t know how to use it positively to build a good society, you are irresponsible. You have become the man that the Yoruba will call alagbara ma mero. When we stop interpreting, interrogating, inspiring, guiding and challenging our country as writers, as journalists, we are also wasting our talents, we are destroying our gifts. And nothing can be more irresponsible than self-destruction.

- Mr Kunle Ajibade, Executive Director of TheNEWS/P.M.NEWS, read this review at the public presentation of Lanre Arogundade’s Media and Election: Professional Responsibilities of Journalists on 16 July 2019 in Lagos.